Autor : Abrate, Vanesa1, CarlĂ©s, Daniel2, Khoury, Marina3, LĂłpez, Ana MarĂa1, Ortiz, MarĂa Cristina5, Wustten, Sebastián6

1 Hospital Universitario Privado de CĂłrdoba,

2Pulmonologist, Chaco,

3Medical Research Institute Alfredo Lanari, University of Buenos Aires,

5Pulmonologist, province of Buenos Aires,

6Hospital San MartĂn, Paraná; Hospital Cullen, Santa Fe

Clinical and Critical Care Section of the AAMR

https://doi.org/10.56538/ramr.ESNJ3391

Correspondencia : Vanesa Abrate. E-mail: abrate.vanesa@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Since there are various guidelines for respiratory diseases, we aimed to

know which are chosen by physicians in their daily clinical practice.

Methods: A descriptive, cross-sectional study was conducted through a

questionnaire sent to pulmonologists of the Argentinian Association of

Respiratory Medicine.

Results: The most commonly used guideline for COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary

disease) was the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD)

(82 %), followed by GesEPOC (51 %). For asthma, the most commonly used guideline was the Global Initiative

for Asthma (GINA) 2022 (89 %) and the Spanish Guideline on the Management of

Asthma (known for its acronym in Spanish, GEMA), GEMA 5.2 (68 %). In

difficult-to-control asthma, GINA 2022 (82 %) and GEMA 2022 (53 %) were used.

With regard to spirometries, 54 % of respondents

favored NHANES III (Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey) and

22 % used theoretical Knudson reference values. For pneumonia, 62 % chose the

guidelines of the SADI (Argentinian Society of Infectious Diseases), 37 %

preferred those of the IDSA (Infectious Diseases Society of America) and 20 %,

chose the guidelines of the BTS (British Thoracic Society). For pulmonary

nodules, 62 % used Fleischner guidelines, and 35 %

favored Lung-RADS 1.1. For hypersensitivity pneumonitis, 83 % selected the

ATS/JRS/ALAT Guidelines (American Thoracic Society/Japanese Respiratory

Society/Latin American Thoracic Society). And with respect to pulmonary

fibrosis imaging, 89 % used ALAT/ERS (EuÂropean Respiratory Society)/JRS

recommendations, and 18 % preferred White Paper.

Discussion: Although there are studies about adherence to guidelines, none of them

shows which are the chosen recommendations within a group of

guidelines of the same topic. In COPD and asthma (including

difficult-to-control asthma) GOLD, GINA and the guidelines of the Spanish

Society of Respiratory Disease (GesEPOC and GEMA)

were chosen. The preference for the national guideline for pneumonia is

consistent with the need to consider local epidemiology.

Key words: Clinical Practice Guidelines, Respiratory Tract Diseases, GOLD, GesEPOC, GINA, GEMA

RESUMEN

IntroducciĂłn:

Dada

la existencia de variadas guĂas para enfermedades respiratorias, se buscĂł conocer

cuáles eligen los mĂ©dicos para utilizar en su práctica clĂnica.

Materiales

y MĂ©todos: se

realizĂł un estudio descriptivo, transversal, mediante una encuesta a neumonĂłlogos de la AsociaciĂłn Argentina de Medicina

Respiratoria.

Resultados:

La

guĂa más utilizada para EPOC fue la Iniciativa Global para la EnfermeÂdad

Pulmonar Obstructiva CrĂłnica (GOLD) (82 %), seguida por GesEPOC

(51 %). Para asma las más usadas fueron la Iniciativa Global para el Asma

(GINA) 2022 (89 %) y GEMA 5.2 (68 %). En asma de difĂcil control, se

prefirieron GINA 2022 (82 %) y GEMA 2022 (53 %). En espirometrĂa,

un 54 % de los respondedores se inclinĂł por NHANES III y un 22 % utilizĂł

valores teĂłricos de referencia de Knudson. En

neumonĂa, el 62 % eligiĂł SADI, el 37 %, IDSA y el 20 %, BTS. Para nĂłdulos

pulmonares, el 62 % prefiriĂł las guĂas Fleischner, 35

% se inclinĂł por Lung-RADS 1.1. Para neumonitis por

hipÂersensibilidad, un 83 % seleccionĂł las guĂas de las sociedades conjuntas

ATS/JRS/ ALAT. Para imágenes de fibrosis pulmonar, el 89 % utilizó

ALAT/ERS/JRS/ALAT y el 18 % White Paper.

DiscusiĂłn:

Si

bien hay estudios sobre adherencia a guĂas, no los hay acerca de preferencias

de utilizaciĂłn entre varias referidas a un mismo tema. En EPOC y asma

(incluyendo la de difĂcil control) se eligieron GOLD y GINA y las de la

Sociedad Española de PatologĂa Respiratoria (GesEPOC

y GEMA). El uso preferencial de la guĂa nacional para neumonĂa es coherente con

la necesidad de contemplar la epidemiologĂa local.

Palabras

clave: GuĂas

de práctica clĂnica, Enfermedades respiratorias, GOLD, GesEPOC,

GINA, GEMA

Received: 09/25/2023

Accepted: 02/05/2024

INTRODUCTION

Clinical practice guidelines

provide a set of standards of care for the diagnosis and treatment of various diseases.

The most common respiratory diseases are addressed by different guidelines,

both national and international. These guidelines are periodically updated

based on new evidence and are advisory in nature for practice.1

Their recipients vary from general

physicians to specialists. Although they may be thought of as opposed to

personalized medicine trends, they actually complement each other since the

application of a guideline is never automatic; it requires taking into account

the characteristics of the patient and their context.1,2 The guidelines themÂselves are the result of

systematic reviews; expert consensus is involved, both in the stage of choosing

the most appropriate questions and in evaluating the results obtained and the

final recommendations.3 Many medical

specialty congresses dedicate part of their time to presenting, discussing, or

updatÂing them, contributing to their dissemination and eventual use.

From the Clinical and Critical

Care Section of the Argentinian Association of Respiratory MediÂcine (AAMR), we

aim to understand which are the specialty guidelines

chosen by pulmonologists asÂsociated with the AAMR.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

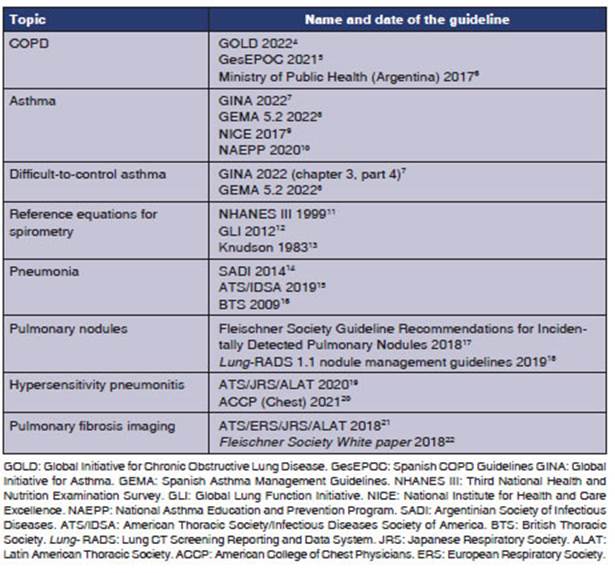

A cross-sectional study was

conducted through an anonÂymous survey of the physicians who are members of the

AAMR. A questionnaire was designed using a form on the Survey Monkey©

platform which included questions about the characteristics of the physicians

and their use of pulmonology guidelines. The researchers selected the most widely

disseminated guidelines for relevant respiratory diseases and other respiratory

topics (Table 1) based upon their criteria. The survey allowed respondents to

select more than one guideline for each topic, because in practiÂce, physicians

make use of elements from one guideline or another, according to their needs.

With the agreement of the AAMR

authorities, 946 active members of the updated roster of pulmonologists as of OctoÂber

25, 2022 were invited to participate via email. Between October 25 and December

15, 2022, the questionnaires were sent out initially and resent up to a maximum

of four times to those who did not respond.

The analysis was conducted using Stata 16.0 software (StataCorp,

Texas, USA). Groups were compared using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact

test, as appropriate. A p-value of <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

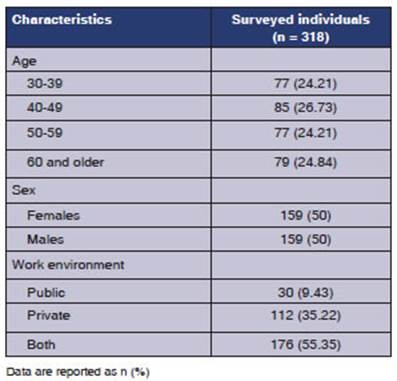

318 completed forms were

obtained, resulting in a response rate of 33.61 %. The characteristics of the

sample are presented in Table 2.

A higher proportion of women was found among respondents under 50 years of age. 59.26 %

(n = 96) of the 162 respondents under 50 years of age and 40.38 % (n = 62) of

the 156 respondents aged 50 or older were women. This difference was

statistically significant (p = 0.001).

Although the public sector as the

sole workÂplace was underrepresented, women and responÂdents under 50 years of

age were predominant in that sector. 73.33 % (n = 22) of the 30 responÂdents

who worked solely in the public sector, 43.75 % (n = 49) of the 112 who worked

in the private sector, and 50 % (n = 88) of the 176 who worked in both sectors

were women (p = 0.016). Similarly, 66.67 % (n = 20) of the 30 respondents who

worked solely in the public sector, 39.29 % (n = 44) of the 112 of the private

sector, and 55.68 % (n = 98) of the 176 respondents who worked in both sectors were under 50 years of age (p = 0.005).

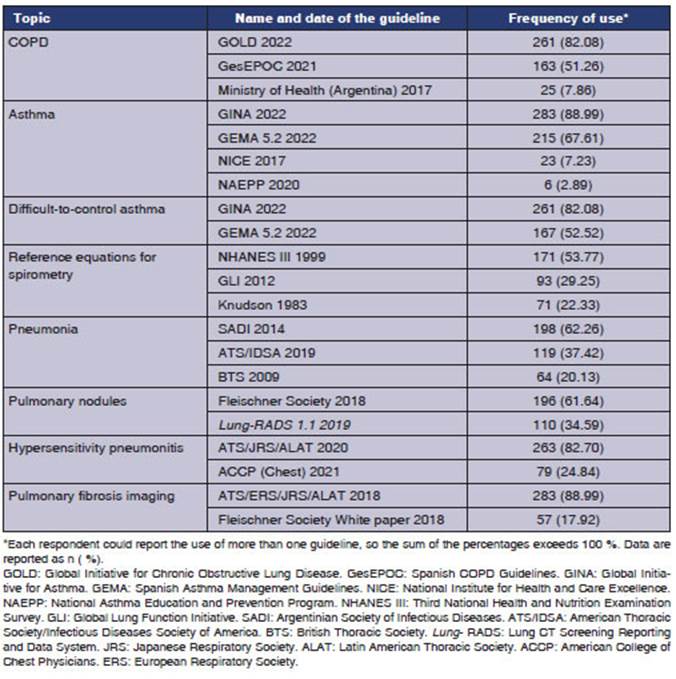

It was common for the

respondents to select more than one guideline for each condition. Table 3 shows

the reported frequency of use for each guideline.

In COPD, the most

commonly used guideline was the GOLD (82 %), followed by GesEPOC

(51 %); and the least consulted was the one from the Ministry of Health of the

Nation (8 %). For asthma, the most frequently chosen guidelines were GINA 2022

(89 %), GEMA 5.2 (68 %), NICE (7 %), and NAEPP (2 %). In difficult-to-control

asthma, GINA 2022 (82 %) and GEMA 2022 (53 %) were mostly used. In relation to spirometries, 54 % of respondents chose NHANES III and 22 %

used theoretical Knudson reference values. For pneuÂmonia, 62 % chose the

guidelines of the SADI, 37 % preferred those of the IDSA and 20 %, chose the

BTS. For pulmonary nodules, 62 % of respondents used Fleischner

guidelines, and 35 % favored Lung-RADS 1.1. For hypersensitivity pneumonitis,

83 % selected the ATS/JRS/ALAT Guidelines, and 25 % chose the AACP (American

Association of Chest Physicians). Regarding pulmonary fibrosis imaging, 89 %

used ALAT/ERS/JRS recommendaÂtions, and 18 % preferred White Paper.

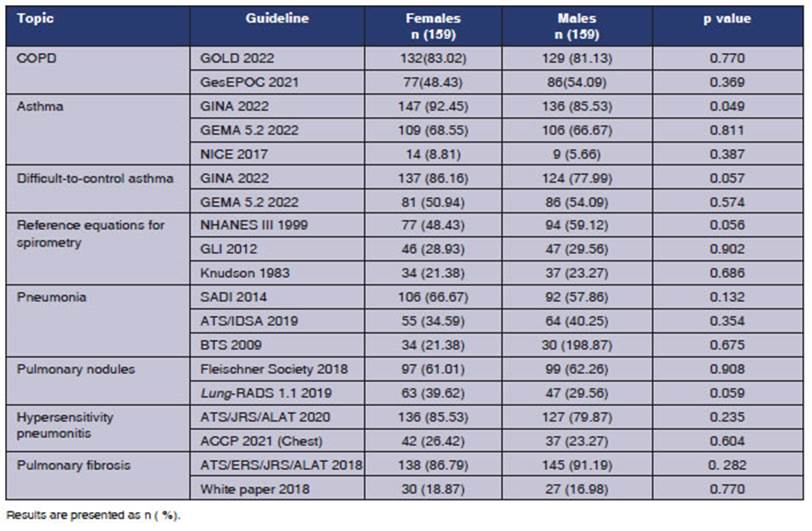

Table 4 compares the

use of guidelines across groups according to gender.

There were no

differences across the groups according to gender in the frequency of use of

most guidelines, with the exception that women reported a higher frequency in the

use of the GINA guidelines for asthma.

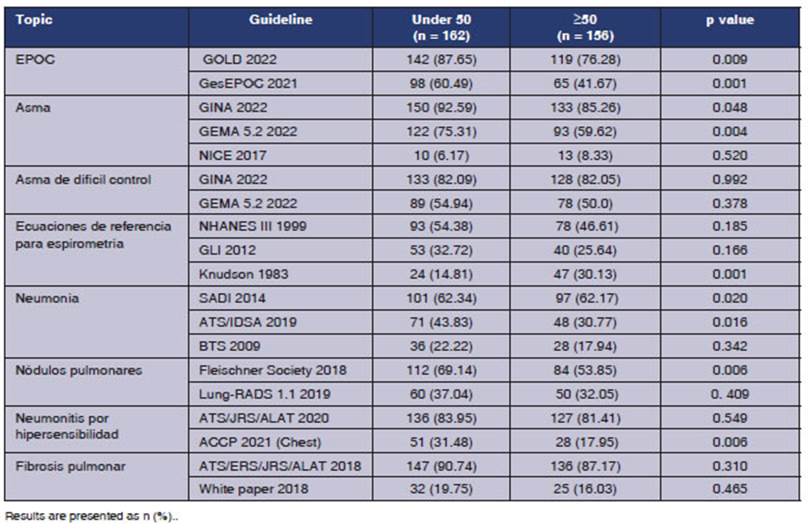

Table 5 compares the use of

guidelines across groups according to age.

Individuals under the age of 50

reported a staÂtistically significant higher usage of the GOLD and GesEPOC guidelines for COPD, the GINA and GEMA 5.2

guidelines for asthma, the GLI 2012 guideline for spirometry,

the ATS/IDSA 2019 guideline for pneumonia, and the Fleischner

Society 2018 and ACCP 2021 (Chest) guidelines for hypersensitivity pneumonitis

incidental nodÂules. Regarding spirometries, the

group over 50 reported higher use of Knudson’s theoretical reference values.

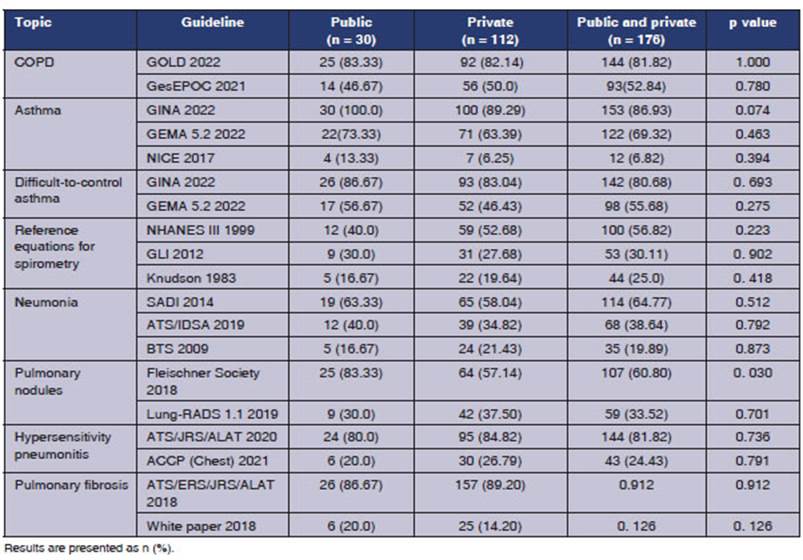

Table 6 compares the use of

guidelines across groups according to the work environment.

There were no significant

differences in the groups that were divided according to work enviÂronment with

regard to the frequency of use of the guidelines for COPD, asthma, difficult-to-control

asthma, spirometry, pneumonia, hypersensitivity

pneumonitis, or lung fibrosis imaging. Regarding lung nodules, the Fleischner guideline was most frequently used in the public

sector.

DISCUSSION

This research is novel as we have

not found any literature that considers usage preferences among different

guidelines for respiratory diseases in our setting. The diseases under

consideration by the respondents reflect the frequency of these diseases in

consultations to pulmonologists. A study conÂducted in a general population

over 40 years of age from six major regions of Argentina (EPOC.AR), which

included the performance of spirometries, revealed a

prevalence of COPD of 14.5 %.23 Asthma is one of the most prevalent

respiratory diseases in Argentina and worldwide.24 In urban areas of

our country, a telephone survey among individuals aged 20 to 44 identified 5.9

% of 1,521 subjects as asthmatic, while 13.9 % reported having wheezÂing.24

Additionally, it is known that around 5 % of the asthmatic population suffers

from severe forms of this condition.25 Given the need to perform spirometries for the diagnosis and monitoring of these and

other conditions, it was considered inÂteresting to explore whether

pulmonologists used the same equations for their reference values when

reporting them.

There are numerous publications

related to levels of adherence to pulmonology guidelines, many of them in their

early versions. This study addresses another aspect, the preference for one

guideline to another, in the context of Argentina, at a time when many of those

guidelines are well-established and some refer to the same topics, thus

providing the possibility of choice.

In COPD, the GOLD guideline dates

back to 2001, with annual updates and major revisions every 5 years. It is

developed by an international panel of healthcare professionals that includes

experts in respiratory medicine, public health, education, and economics, among

other things.26 Its development responds to

the need for a strateÂgic document to provide effective care for COPD patients

globally. An update from 2023 is availÂable with changes in the classification

and some therapeutic strategies, along with a review of the COVID-COPD

association chapter.27 On the other hand, the first version of the GesEPOC guideline was published in 2012.28 While

not substantially different, the development team of GesEPOC

includes members of the Spanish Patients Forum; it proposes a multidimensional

evaluation, and is one of the first guidelines to conduct treatment acÂcording

to clinical phenotypes.28 The latest updates incorporate the concept

of treatable traits, which would allow for a more personalized approach to

medicine. As for the national guideline from the Ministry of Health, it was

developed in 2017, it has not been updated since then, and has not been widely

disseminated.6 In this study, the GOLD Guideline was reported as the

most commonly used guideline for COPD (82 %), followed by GesEPOC

(51 %); and the least consulted was the one from the Ministry of Health of the

Nation (8 %). In individuals under 50 years, the frequency of use of GOLD and GesEPOC was significantly higher, but there were no

differences according to the proÂfessionals’ work environment. A study

conducted among generalist physicians from two New York hospitals identified

barriers to implementing the GOLD 2010 guideline.29 The difficulties

cited by professionals for not adhering to GOLD guidelines included lack of familiarity,

perceived low benefit, time limitations, and occasionally, disagreement.29

In asthma, the GINA guideline

dates back to 1995, with annual updates since 2002.30 The most recent updates include a significant change in the

management of mild asthma, the first of the five treatment steps, which

relegates short-acting beta 2 agonists (SABAs) to alternative rather than sugÂgested

treatment for exacerbations. The GEMA guideline, whose first edition dates back

to 1997, recognizes six therapeutic steps and, although it allows for combined

treatment with inhaled cortiÂcosteroids, it maintains the use of SABAs as

rescue medication; there is a more detailed breakdown of the treatment for

severe forms in step 6.31 The NICE guideline, of British origin, has

a wide range of recipients (generalist physicians, nurses, proÂfessionals in

secondary and tertiary care services for asthma, patients, and families, among

others) and is organized based on a thematic index.9 The NAEPP

guideline, of American origin, is aimed at professionals and is presented in

the form of quesÂtions, for which answers are given with their level of

evidence and recommendations. 10 It allows for a focused

consultation for a specific problem in the practice. In the present study, the

most reported guidelines were GINA 2022 (89 %) and GEMA 5.2 (68 %), and

respondents under 50 years were the ones who chose them the most. A joint

statement by the ERS and the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical

Immunology (EAACI) warned about suboptimal adherence to these guidelines interÂnationally

and emphasized the need to consider different real-life contexts.32

In difficult-to-control asthma,

GINA 2022 (82 %) and GEMA 2022 (53 %) were mostly used. While

patients are usually assisted in reference centers, respondents report using

the same genÂeral asthma guidelines (GINA and GEMA). There are also

guidelines for difficult-to-control asthma developed by ALAT, which is one of

the societies incorporated into the GEMA guidelines, that is why they were not

specifically consulted in this survey.33

Regarding reference equations for

spirometry, the use of one or the other can affect

the diagnosis of airway obstruction and the estimation of its seÂverity.34

One of the oldest, the Knudson equation, was based on a North American white

population; 746 patients aged 8 to 90, and emerged to detect diseases in

textile workers due to cotton expoÂsure.35 It was later expanded to

include African Americans but not Latin Americans. In 2005, the ATS and ERS

recommended the use of the equaÂtion known as NAHNES III for US patients aged

between 8 and 80 years.34 In order to extend the reference to other

groups, the GLI 2012 included 57,395 Caucasians, 3,545 African Americans, and

13,247 Asians; the age range extended from 3 to 95 years.12 These

last two equations have shown good correlation with each other for average

adults, which is not the case when dealing with patients older than 80 years,

particularly those of extreme heights (very short or very tall).34 A

study conducted in Chile included the comparison of the Knudson equation (the

most commonly used by laboratories in that country) with the Gutiérrez 2014

equation (designed for the Chilean populaÂtion) and GLI 2012, in 315 subjects

over 40 years, smokers or ex-smokers, healthy or with COPD, and found good

correlation between the three.36 It has been suggested that the

Knudson equation underestimates restriction compared to NHANES III.36

In Argentina, functional measurements were performed on 105 women and 132 men

from the Capital City and Metropolitan Area of Buenos AiÂres, between 18 and 86

years old, and the Lower Limit of Normality (LLN) was determined as a variable

percentage for each parameter, at each age, and at each height, thus

eliminating the concept of a fixed percentage value, which led to underdiagnosis in younger individuals and overÂdiagnosis in older ones.37 In Mendoza, a

similar study was carried out on 103 healthy volunteers, aged 15 to 65 years,

who underwent spirometry, and a smaller number

underwent peak expiratory flow, measurements of mean inspiratory and expiÂratory

pressures (MIP and MEP), and a 6-minute walk test.38 Good

correlation was found between NHANES and the Mendoza sample, especially in spirometric values, except for the FEV1/FVC ratio (forced

expiratory volume in the first second/forced vital capacity) where the LLN was

a better option for defining normality.38

In our work, the most commonly

used equation was NHANES III, which may be related to the fact that most spirometry equipment has it incorÂporated into their

software. The increased use of the GLI equation among young people could be

explained by the fact that it includes multiethnic groups, has a wider age

range (3 to 95 years), and was gradually included in new equipment.12

ConÂversely, the use of the Knudson equation, which is used by one-fifth of the

respondents, predominates among those over 50 years and may be attributed to

the age of the equipment or to the lesser flexibilÂity in adapting to changes

found in this age group.

In pneumonia, the national

guideline of SADI was the most commonly used among our responÂdents, despite

not being updated since 2014. This is attributed to the fact that, it being an

infecÂtious disease, local epidemiological factors and available antibiotics in

our country are taken into account as well as being more user-friendly due to

its concise nature and for being in the Spanish language. Gatarello

et al studied the adherence of respondents to the IDSA/ATS pneumonia guideÂline

and included 36 Latin American physicians.39

Treatment was considered appropriate in 30.6 % of prescriptions for

community-acquired pneumonia. The use of antibiotics with inadequate

spectrum, monotherapy, or coverage not indicated for

multiÂdrug-resistant organisms was considered as lack of adherence. In the case

of nosocomial pneumonia, compliance with the IDSA/ATS guidelines was only 2.8 %

(monotherapy and lack of dual antibiotic treatment

against Pseudomonas aeruginosa).39

Regarding pulmonary nodules, the

most freÂquently chosen guideline was the Fleischner

Society 2018, which was developed for the manÂagement of incidental nodules,

that is to say, those appearing during a chest CT scan for any requested

reason.17 Its goal is to limit further evaluations of nodules with

very low probability of cancer (<1 %) and not overlook them if the

probability is ≥1 %.17 Hedstrom et

al studied the adherence of radiologists and clinicians to the Fleischner Society guidelines with regard to the management

of incidental lung nodules and found that around 5 % conducted a more

aggressive follow-up and in 9 % of the cases, the follow-up was less aggressive

than recommended.40 In contrast, Lung-RADS is oriented towards the management

of nodules found during screening, corresponding to indiÂviduals with

sufficient risk to qualify for these programs.18 Moreover, the

number of centers curÂrently conducting screening in our country is not high,

hence the lower familiarity with Lung-RADS.

When analyzing guidelines for

hypersensitivity pneumonitis, a clear preference is observed for the 2020

ATS/JRS/ALAT guidelines. Its dissemination during the pandemic and its temporal

precedence over the ACCP guidelines could explain this choice. Among those who

chose the ACCP guidelines, the ones under 50 years prevailed. As already menÂtioned, the study protocol allowed for opting for

more than one guideline, according to the needs.

With regard to the images

supporting the diagÂnosis of pulmonary fibrosis, the use of ALAT/ERS/ JRS was

predominant, and this can be attributed to its wider dissemination and the fact

of havÂing been elaborated by multiple societies, which provides more

robustness. However, there are no major differences between these guidelines

and the Fleischer Society White paper. Both identify key questions and provide

radiological and tissue images that are prototypical of each proposed category.

The latter adds a checklist at the end to rule out alternative diagnoses.

Several authors of

hypersensitivity pneumonitis and pulmonary fibrosis guidelines warn in a recent

publication that, as each guideline is developed independently, they do not

reflect the physician’s needs when faced with a patient who does not yet have a

diagnosis and is within a spectrum of fiÂbrotic diseases that may include both

conditions.43 With a pragmatic approach, they suggest using an

algorithm that integrates these two guidelines and includes both clinical,

radiological, and pathologiÂcal features to distinguish hypersensitivity

pneumonitis from pulmonary fibrosis.41

In general terms, although

respondents were not asked to justify their choice, it can be specuÂlated that

professionals’ preference for different guidelines is due to the fact that they

were origiÂnated from well-known societies, which respond to a rigorous and

updated review of the best available scientific evidence. In the case of the

Argentine guideline on pneumonia, the local relevance of the recommendations is

privileged. Another factor that may determine the choice is the availability of

the equipment or supplies suggested in the stanÂdards, because if they are not

available, the guideÂline is less applicable. Finally, once professionals

become familiar with one particular guideline and have experience with it, they

incorporate updates more naturally.

This study acknowledges

limitations, mainly the number of respondents, given that only 33 % of those

who received the survey responded. It was conducted among pulmonology

specialists from the AAMR, excluding other specialties or pulmonoloÂgists not

associated. There is also the limitation of having omitted some guidelines that

are possibly used. Recently, the ERS/ESICM (European Society of Intensive care

Medicine)/ESCMID (European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious

Diseases)/ALAT have released a guideline for the management of severe

community-acquired pneuÂmonia, which has not been part of our survey.42

However, their results allow us

to explore the current reality regarding the use of the guidelines and make

some general recommendations. The need to use updated guidelines is emphasized,

as this improves the quality of care, increases patient safety, provides legal

and juridical support for professionals, and optimizes cost-effectiveness.

Scientific societies together with national health authorities should encourage

guideline update and availability. Likewise, treatments proposed with strong

evidence should be available in the country, avoiding dissociation between

recommendations and daily practice. Referring specifically to one of the

guidelines subjected to the survey in this research, we suggest that the GLI spirometric reference equation is used in our equipment,

for the advantages mentioned before. Similarly, it would be of high priority to

update the national guideline for acute community-acquired pneumoÂnia, with the

participation of all societies involved in its management.

In conclusion, an analysis of the

situation has been described as of the end of 2022 regarding the use of

guidelines for prevalent respiratory diseases by a group of 318 pulmonologists

who are members of the AAMR. Although there is a trend among respondents under

50 to use the most recent guidelines, the use of updates from long-standing

guidelines of the main scientific societies in the specialty, such as GOLD in

COPD, GINA in asthma, and SADI in pneumonia, remains very strong in all groups.

Acknowledgement

To the authorities of

the AAMR, to the secretaries of the AAMR, and the webmaster Muriel Cabrera.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of

interest to declare that are relevant to this publication.

REFERENCES

1. Soler-Cataluña

JJ. Clinical practice guidelines or personalÂized medicine in

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease? Arch Bronconeumol (Engl Ed).

2018;54:247-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arbres.2017.08.002

2. Goldberger JJ, Buxton AE. Personalized medicine vs guideÂline-based

medicine. JAMA.

2013;309:2559-60.

https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.6629.

3.

Grupo de trabajo para la actualizaciĂłn del Manual de ElaboÂraciĂłn de GPC.

ElaboraciĂłn de GuĂas de Práctica ClĂnica en el Sistema Nacional de Salud.

ActualizaciĂłn del Manual MetodolĂłgico [Internet]. Madrid: Ministerio de

Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad; Zaragoza: Instituto Aragonés de

Ciencias de la Salud (IACS); 2016. Disponible en: http://portal.guiasalud.es/emanuales/elaboracion_2/?capitulo.

4. Venkatesan P. GOLD report:

2022 update. Lancet Respir Med. 2022;10: e20.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00561-0.

5.

Miravitlles M, Calle M, Molina J, et al. Spanish COPD Guidelines (GesEPOC)

2021 Updated PharmacologiÂcal treatment of stable COPD. Arch Bronconeumol. 2022;58:69-81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arbres.2021.03.005

6.

Argentina. Ministerio de Salud de la NaciĂłn. GuĂa breve de EPOC. —1a ed.— Ciudad AutĂłnoma de Buenos Aires: Ministerio de Salud de

la NaciĂłn, 2017. 40p.

7. Global Initiative for Asthma. Global strategy for asthma management and prevention. 2022. Disponible en:

www.ginasthma.org

8.

Sociedad Española de NeumologĂa y CirugĂa Torácica. GEMA 5.2 GuĂa Española para

el manejo del asma. 2022. Disponible

en: www.gemasma.com

9. National Institute for Health

and Care Excellence (NICE). Asthma: diagnosis, monitoring and chronic asthma

manÂagement. London; 2021 Mar 22. PMID: 32755129. Nice 2017

10. National Asthma Education and

Prevention Program. Expert Panel Report: Guidelines for the Diagnosis and

Management of Asthma. Bethesda, Maryland: National Heart, Lung, and Blood

Institute, National Institutes of Health. 2020.

11. Hankinson JL, Odencrantz JR, Fedan KB. Spirometric reference values from a sample of

the general U.S. populaÂtion. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;159:179-87.

https://doi.org/10.1164/ajrccm.159.1.9712108.

12. Quanjer

PH, Stanojevic S, Cole TJ, et al; ERS Global Lung

Function Initiative. Multi-ethnic reference values for spiÂrometry

for the 3-95-yr age range: the global lung function 2012 equations. Eur Respir J. 2012;40:1324-43. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00080312.

13. Knudson RJ, Lebowitz MD, Holdberg CJ, Burrows

B. Changes in normal maximal expiratory flow-volume curve with growth and

aging. Changes in the normal maximal expiratory flow-volume curve with growth

and aging. Am

Rev Respir Dis. 1983;127:725-34.

14.

Lopardo G, BasombrĂo A,

Clara L, Desse J, De Vedia

L, Di Libero E, et al. NeumonĂa adquirida de la comunidad en adultos.

Recomendaciones sobre su atenciĂłn. Medicina (Buenos Aires). 2015;75:245-57.

15. Metlay

JP, Waterer GW, Long AC, et al. Diagnosis and TreatÂment

of Adults with Community-acquired Pneumonia. An Official

Clinical Practice Guideline of the American ThoÂracic Society and Infectious

Diseases Society of America. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019; 200:e45-e67.

https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201908-1581ST.

16. Lim WS, Baudouin

SV, George RC, et al. Pneumonia GuideÂlines Committee of the BTS Standards of

Care Committee. BTS guidelines for the management of community acquired

pneumonia in adults: update 2009. Thorax. 2009;64 Suppl 3:iii1-55.

https://doi.org/10.1136/thx.2009.121434.

17. Bueno

J, Landeras L, Chung JH. Updated Fleischner Society Guidelines for Managing Incidental

Pulmonary Nodules: Common Questions and Challenging Scenarios. Radiographics.

2018;38:1337-50.

https://doi.org/10.1136/thx.2009.121434

18. ACoR.

ACR Lung-RADS - Update 1.1 2019. 2019. DisÂponible en:

https://www.acr.org/-/media/ACR/Files/RADS/Lung-RADS/LungRADS-1-1-updates.pdf?la=en.

https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.2018180017

19. Raghu G, Remy-Jardin M, Ryerson CJ, et al. Diagnosis of Hypersensitivity

Pneumonitis in Adults. An Official ATS/ JRS/ALAT Clinical

Practice Guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202(3):

e36-e69. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.202005-2032ST.

20. Fernández

PĂ©rez ER, Travis WD, Lynch DA, Brown KK, Johannson

KA, Selman M, et al. Diagnosis and Evaluation of Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis:

CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. Chest. 2021;160(2):e97-e156.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2021.03.066.

21. Raghu G, Remy-Jardin M, Myers JL, et al. American Thoracic Society,

European Respiratory Society, JapaÂnese Respiratory Society, and Latin American

Thoracic Society. Diagnosis of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis.

An Official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Clinical Practice Guideline.

Am J Respir Crit Care Med.

2018;198:e44-e68.

https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201807-1255ST.

22. Lynch DA, Sverzellati

N, Travis WD, et al. Diagnostic criteÂria for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a Fleischner Society White Paper. Lancet Respir

Med. 2018;6:138-53.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(17)30433-2.

23.

Echazarreta AL, Arias SJ, Del Olmo R, et al; Grupo de

estudio EPOC.AR. Prevalencia de enfermedad pulmoÂnar obstructiva crĂłnica en 6

aglomerados urbanos de Argentina: el estudio EPOC.AR. Arch

Bronconeumol (Engl Ed).

2018;54:260-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.

arbres.2017.09.018.

24. Arias SJ, Neffen

H, Bossio JC, et al. Prevalence and FeaÂtures of

Asthma in Young Adults in Urban Areas of ArgenÂtina. Arch Bronconeumol (Engl Ed).

2018 Mar;54(3):134-9.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arbres.2017.08.021.

25. Shah PA, Brightling

C. Biologics for severe asthma-Which, when and why? Respirology. 2023;28:709-21. https://doi.org/10.1111/resp.14520.

26. Mirza

S, Clay RD, Koslow MA, Scanlon PD. COPD Guidelines: A

Review of the 2018 GOLD Report. Mayo Clin Proc. 2018;93:1488-502. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.05.026.

27. Global Initiative for Chronic

Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD), Global strategy for the diagnosis, management,

and prevention of chronic obstructive lung disease (2023 Report).

https://goldcopd.org/2023-gold-report-2/

28.

Miravitlles M, Soler-Cataluña JJ, Calle M, et al.

GuĂa Española de la EPOC (GesEPOC).

Tratamiento farmaÂcolĂłgico de la EPOC estable [Spanish

COPD Guidelines (GesEPOC): Pharmacological treatment of stable COPD]. Aten Primaria. 2012;44:425-37.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aprim.2012.04.005.

29.

PĂ©rez X, Wisnivesky JP, Lurslurchachai

L, Kleinman LC, Kronish IM.

Barriers to adherence to COPD guidelines among primary

care providers. Respir Med. 2012;106:374-

81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2011.09.010.

30. Bateman ED, Hurd SS, Barnes PJ, et al. Global strategy for asthma

management and prevention: GINA execuÂtive summary. Eur Respir J.

2008;31:143-78. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00138707.

31.

Hidalgo PP. Asma: GINA 2022 vs Gema 5.2. Respiratorio en AtenciĂłn Primaria No.

2. Revista online disponible en:

https://www.livemed.in/canales/respiratorio-en-la-red/respiratorio-atencion-primaria/numero-2/asma-gina-2022-gema-5-2.html#:~:text=Tanto%20la%20GINA%20(Global%20Initiative,la%20gu%C3%ADa%20GEMA%20es%20espa%C3

%B1ola

32. Mathioudakis

AG, Tsilochristou O, Adcock IM, et al. ERS/ EAACI

statement on adherence to international adult asthma guidelines. Eur Respir

Rev. 2021;30:210132.

https://doi.org/10.1183/16000617.0132-2021.

33.

GarcĂa G, Bergna M, Vásquez JC, et al. Severe asthma: adding new evidence - Latin American Thoracic SoÂciety.

ERJ Open Res. 2021;7:00318-2020.

https://doi.org/10.1183/23120541.00318-2020.

34. Linares-Perdomo

O, Hegewald M, Collingridge

DS, et al. Comparison of NHANES III and ERS/GLI 12 for airway obstruction

classification and severity. Eur Respir

J. 2016;48:133-41.

https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.01711-2015.

35. LĂłpez

A, Benavides-Cordoba V, Palacios M. Effects of changÂing reference values on

the interpretation of spirometry for rubber workers. Toxicol Rep. 2023;10:686-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxrep.2023.05.011.

36.

Dreyse J, Gil R. Ecuaciones de referencia para

informe de espirometrĂas. ÂżSerá tiempo de adoptar las

ecuaciones de la Global Initiative for Lung Function?

Rev Chil Enferm Respir. 2020;36: 13-7. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0717-73482020000100013

37.

GalĂndez F, SĂvori M,

GarcĂa O, et al. Valores espiromĂ©triÂcos normales

para la Ciudad de Buenos Aires. Medicina (Buenos Aires) 1998;58:141-6.

38.

Lisanti R, Gatica D, Abal

J, et al. ComparaciĂłn de las prueÂbas de funciĂłn pulmonar en poblaciĂłn adulta

sana de la Provincia de Mendoza, Argentina, con valores de referencia

internacionales. Rev Am Med

Respir 2014;14:10-9.

39.

Gattarello S, RamĂrez S, Almarales

JR, Borgatta B, LaÂgunes L,

Encina B, Rello J; investigadores del CRIPS. Causes of non-adherence to therapeutic guidelines in

severe community-acquired pneumonia. Rev Bras Ter Intensiva.

2015;27:44-50.

https://doi.org/10.5935/0103-507X.20150008.

40. Hedstrom

GH, Hooker ER, Howard M, et al. The Chain of Adherence for Incidentally

Detected PulÂmonary Nodules after an Initial Radiologic Imaging Study: A

Multisystem Observational Study. Ann Am Thorac Soc.

2022;19:1379-89.

https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.202111-1220OC.

41. Marinescu

DC, Raghu G, Remy-Jardin M, et al. Integration and

Application of Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Diagnosis of Idiopathic

Pulmonary Fibrosis and Fibrotic Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis. Chest. 2022;162:614-29.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2022.06.013.

42. Martin-Loeches

I, Torres A, Nagavci B, et al. ERS/ESÂICM/ESCMID/ALAT

guidelines for the management of severe community-acquired pneumonia. Eur

Respir J. 2023;61:2200735. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.00735-2022